Turning off lights helps migrating birds

By Deborah Huth Price

Reprinted from the April issue of the Lyons Redstone Review

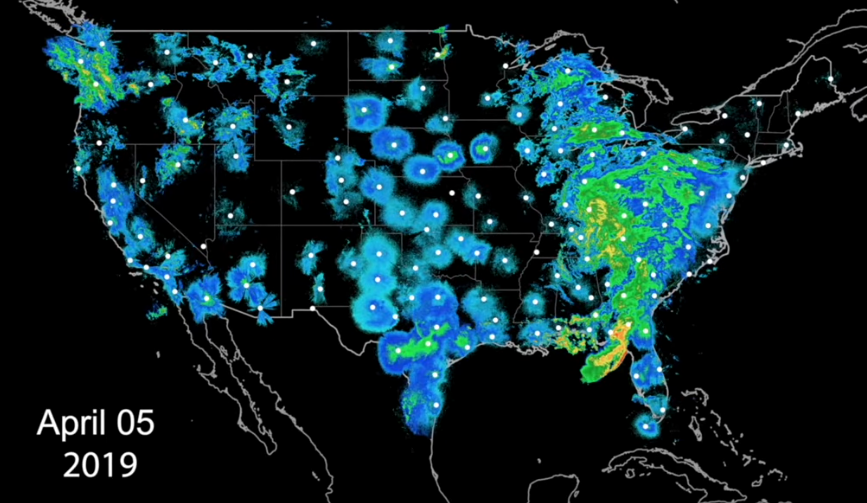

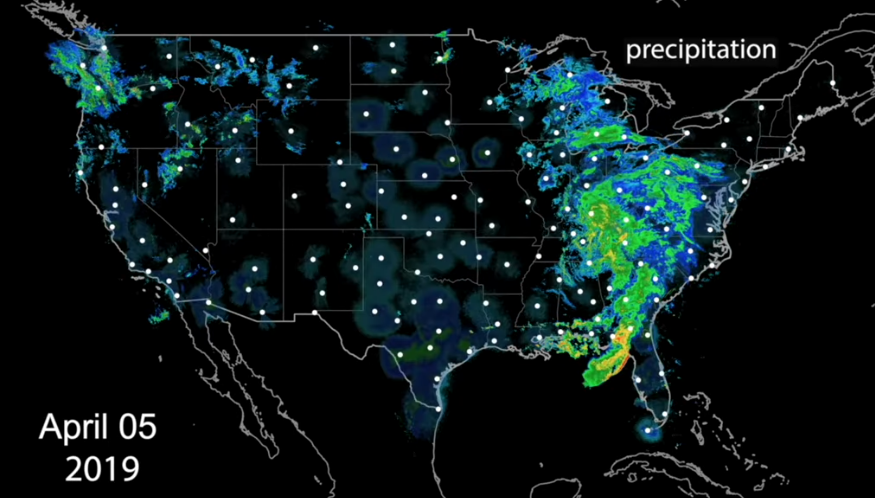

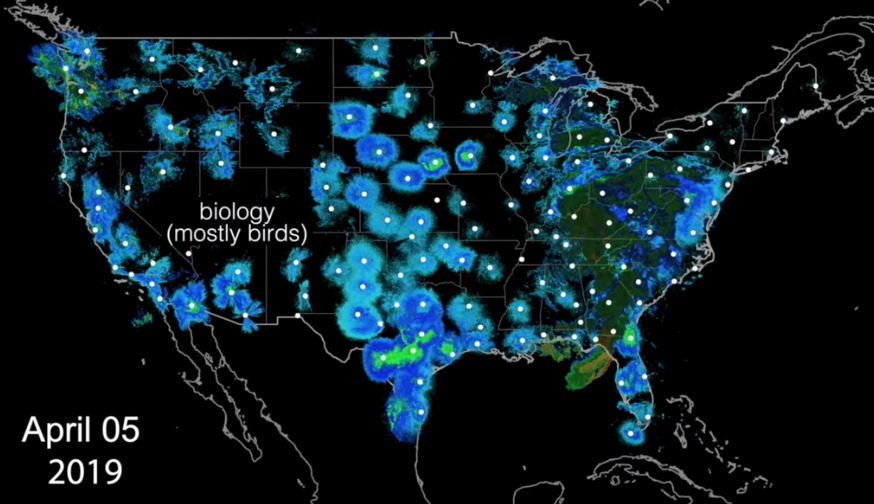

Spring bird migration is in full swing, and while you may see some flocks of birds flying overhead on their journeys, most of these travelers fly unseen after dark.

It may seem counterintuitive that songbirds migrate without the light of day, but there are some good reasons for flying at night. Temperatures are cooler and winds are generally less turbulent. Fewer predators like hawks and eagles are active. In addition, it seems that many birds use cues from the moon and starlight to navigate, and their awareness of magnetic fields seems to be better after dark.

The beautiful little blue Indigo Bunting is an example. This bird was studied extensively in the 1960s and it was found that it follows not only the north/south view of the stars, but the star patterns themselves as they appear to move across the sky.

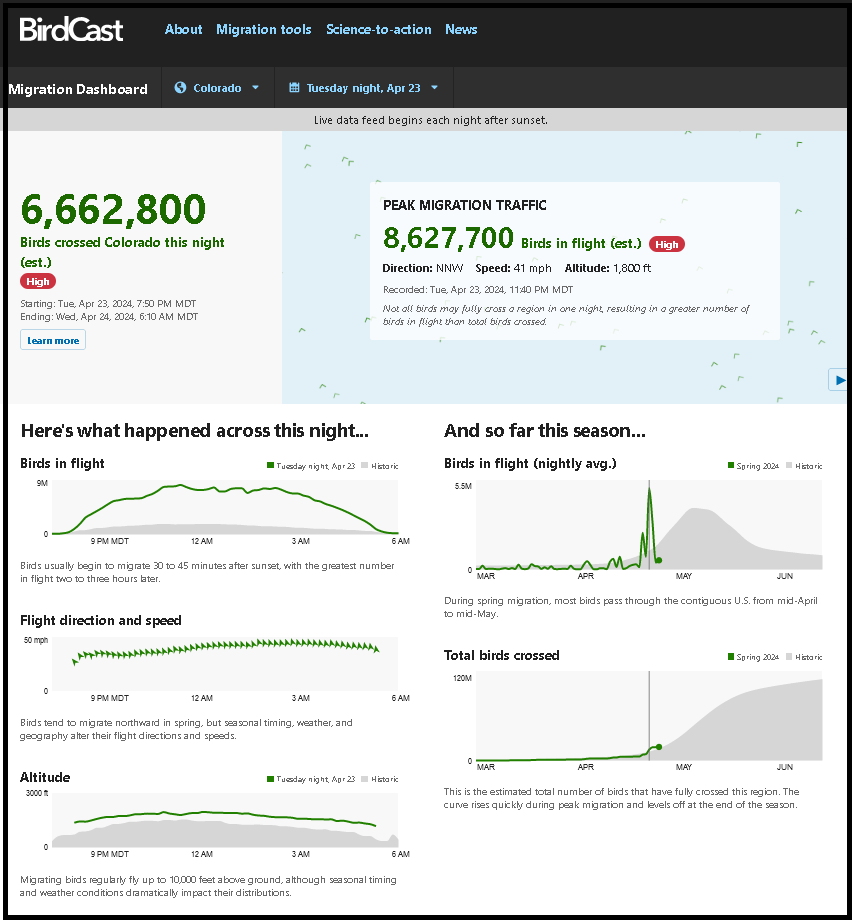

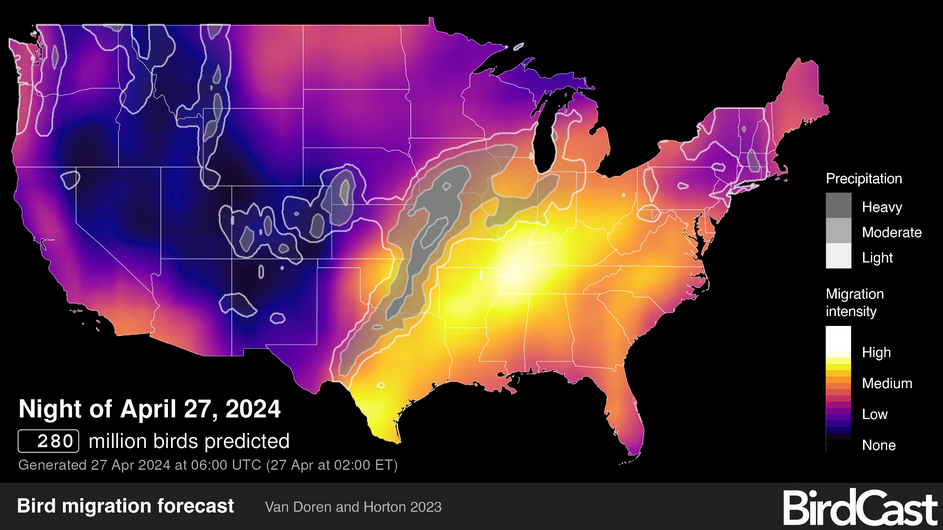

Spring and fall are some of the biggest migratory times for birds. Millions of birds cross our Colorado skies each night during these seasons. Spring migration usually runs from about March 1 through June 15 with peak migration hitting Colorado around the first week in May. The Front Range is along the central flyway for many migrating birds, and at the peak, there can sometimes be billions of birds in one night crossing our state. Compare that to the fact that only about six million people live in Colorado. Fall migration lasts from roughly August 15 through November 30.

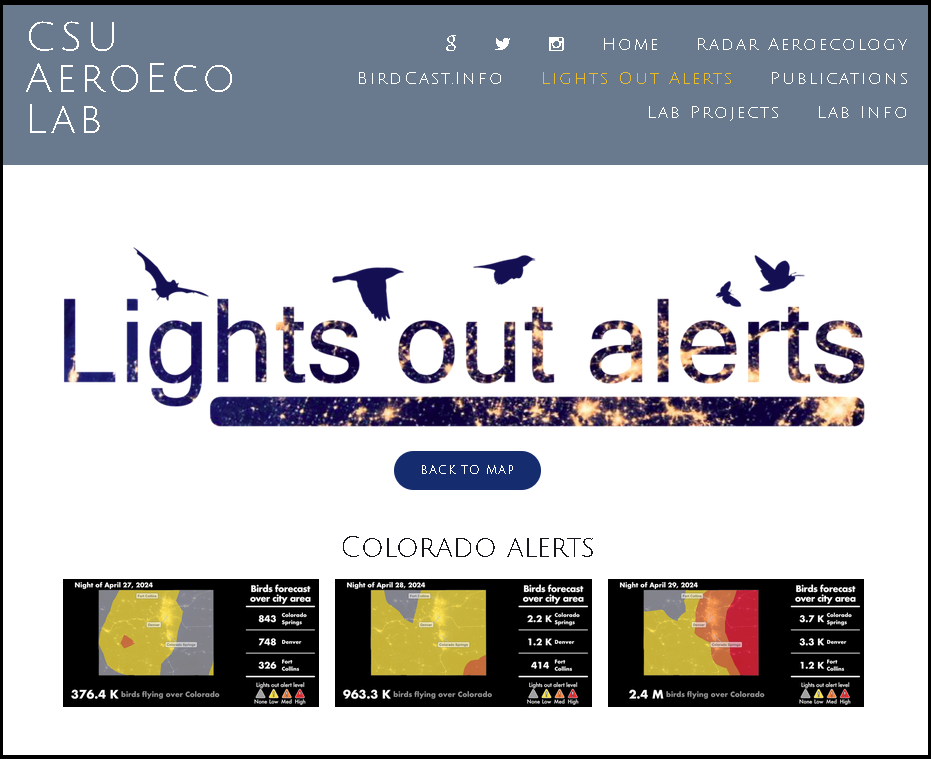

To keep up with the migratory birds and flight numbers, visit https://birdcast.info/, a project organized by Cornell Lab or Ornithology and the National Aubudon Society, among other organizations. You can look up specific counties within Colorado to see how many birds migrate across an area each night.

Some of the species currently migrating overhead, according to the National Aubudon Society, are the American avocet, several species of ducks, tree sparrows, eastern phoebe, lesser yellowlegs, and Baird’s sandpiper, to name a few.

One of the best ways to support our migratory friends is to do the simple act of turning off lights at night. Artificial light confuses and attracts birds as they try to follow natural light, often causing them to get off course, and worse—to crash into buildings. In larger metropolitan areas with skyscrapers and downtown lights, thousands of dead birds are sometimes found in the morning during migratory seasons, after crashing into buildings during flight.

Many metropolitan area residents such as Denver have joined Lights Out campaigns to help migratory birds by encouraging businesses to turn off lights at night. Lights Out Denver estimates that more than 300 bird species migrate through or nest in the city. In addition to turning off lights, Lights Out Denver encourages businesses to install bird-friendly decals on windows to help birds see the glass. They also work towards creating legislation and city ordinances that address bird-friendly building designs.

While residential areas are not as harmful to birds as large cities, artificial light can still be confusing and harmful. Simple things we can all do include turning off non-essential lighting during migratory periods.

DarkSky International suggests five lighting principles to consider: Use light only where it is needed with a clear purpose, shield light so that it is targeted where appropriate (and not just shining into the sky), use the lowest level of light required, use timers or motion detectors, and use warmer colored lights (like amber or red).

World Migratory Bird Day is May 10. One of the local celebrations of migrating birds happens at Walden Ponds Wildlife Habitat in Boulder Saturday, May 17, 9 a.m.-1:30 p.m.

While birds are flying to new feeding grounds for the summer, we can give them a hand by simply flipping a switch.

Deborah Huth Price is an environmental educator, living in Pinewood Springs. Follow her blog at www.walk-the-wild-side.blog or contact her at [email protected].